photosynthesis and cellular respiration study guide

Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration: A Comprehensive Study Guide

This guide delves into the interconnected processes of photosynthesis and cellular respiration, exploring how organisms capture and utilize energy.

It examines the roles of chloroplasts and mitochondria, alongside irradiance, temperature, and hydration impacts on these vital biological functions.

Understanding these processes is crucial for comprehending energy flow and nutrient cycling within ecosystems, as well as the implications for human health and environmental sustainability.

Life’s fundamental processes hinge on energy transformations. Organisms require a constant influx of energy to fuel growth, reproduction, and maintain internal order. This energy originates primarily from the sun, captured through photosynthesis, a process utilized by plants, algae, and some bacteria. Photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy stored in organic molecules, like glucose.

However, this stored energy isn’t directly usable by most cells. Cellular respiration steps in to release this chemical energy in a controlled manner, making it available for cellular work. This process breaks down organic molecules, ultimately generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s primary energy currency.

These two processes are intrinsically linked. Photosynthesis creates the fuel (glucose) and oxygen that cellular respiration requires, while cellular respiration produces carbon dioxide and water – the raw materials for photosynthesis. This cyclical relationship forms the foundation of most ecosystems, driving energy flow and nutrient cycling. Understanding these processes is vital for comprehending the interconnectedness of life and the delicate balance within our environment. The study of these processes also reveals how organisms adapt to varying conditions, like irradiance, temperature, and hydration levels, impacting their efficiency.

II. Photosynthesis: Capturing Light Energy

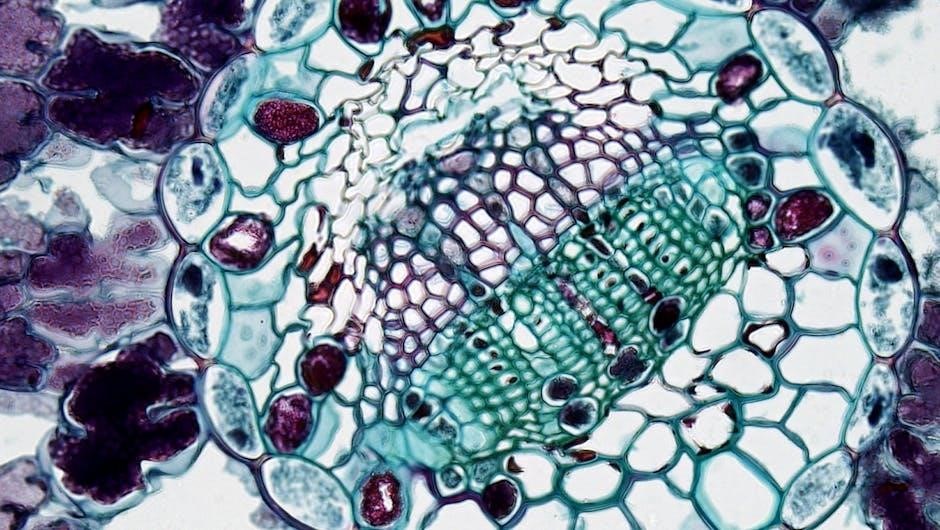

Photosynthesis is the remarkable process by which light energy is converted into chemical energy. It’s not a single step, but a complex series of reactions occurring within chloroplasts, organelles found in plant cells. These chloroplasts contain chlorophyll, a pigment that absorbs specific wavelengths of light – primarily red and blue – while reflecting green light, giving plants their characteristic color.

The overall equation for photosynthesis is deceptively simple: 6CO2 + 6H2O + Light Energy → C6H12O6 + 6O2. However, this masks the intricate steps involved. Essentially, plants take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water from the soil, and using light energy, produce glucose (a sugar) and release oxygen as a byproduct.

The efficiency of photosynthesis isn’t constant; it’s influenced by factors like light intensity, carbon dioxide concentration, and temperature. Understanding how these factors interact is crucial for maximizing plant growth and productivity. Furthermore, the process is divided into two main stages: light-dependent reactions and light-independent reactions (the Calvin cycle), each with distinct requirements and outputs, working in harmony to capture and store solar energy.

III. The Two Stages of Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis unfolds in two interconnected stages: the light-dependent reactions and the light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle). These stages occur in different parts of the chloroplast, demonstrating a remarkable division of labor. The light-dependent reactions, as the name suggests, require light directly and take place within the thylakoid membranes.

Here, light energy is absorbed by chlorophyll and other pigments, driving the splitting of water molecules. This process releases oxygen as a byproduct, generates ATP (adenosine triphosphate – the cell’s energy currency), and NADPH (a reducing agent). These energy-rich molecules, ATP and NADPH, then fuel the subsequent stage.

The light-independent reactions, or Calvin cycle, occur in the stroma, the fluid-filled space surrounding the thylakoids. This stage doesn’t directly require light, but relies on the ATP and NADPH produced during the light-dependent reactions. Carbon dioxide is “fixed” – incorporated into an organic molecule – and ultimately converted into glucose, completing the process of energy storage. The cycle regenerates its starting molecule, allowing it to continue functioning.

IV. Light-Dependent Reactions

The light-dependent reactions are the initial phase of photosynthesis, converting light energy into chemical energy. These reactions occur within the thylakoid membranes inside chloroplasts, utilizing specialized pigment molecules like chlorophyll to capture photons of light. This absorbed light energy excites electrons within the chlorophyll, initiating a chain of events.

Water molecules (H₂O) are split through a process called photolysis, releasing electrons to replenish those lost by chlorophyll, generating oxygen (O₂) as a byproduct, and contributing protons (H⁺) to the thylakoid lumen. The energized electrons move through an electron transport chain, releasing energy that is used to pump protons across the thylakoid membrane, creating a proton gradient.

This proton gradient drives ATP synthase, an enzyme that phosphorylates ADP to produce ATP – a process known as chemiosmosis. Simultaneously, electrons are ultimately accepted by NADP⁺, reducing it to NADPH. Both ATP and NADPH, the energy-carrying molecules, are then utilized in the subsequent light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle) to synthesize glucose.

V. Photosystems I and II

Photosystems I (PSI) and II (PSII) are protein complexes embedded within the thylakoid membranes, crucial for capturing light energy during the light-dependent reactions. PSII functions first, absorbing light optimally at 680nm, initiating the electron transport chain. It utilizes light energy to oxidize water, releasing oxygen, protons, and electrons.

These electrons travel through a series of electron carriers to PSI, which absorbs light optimally at 700nm. PSI re-energizes the electrons, ultimately passing them to NADP⁺, reducing it to NADPH. Each photosystem contains a reaction center chlorophyll molecule – P680 in PSII and P700 in PSI – which become energized upon absorbing light.

Antenna pigments surrounding the reaction center funnel light energy towards it, maximizing light capture efficiency. The coordinated action of PSII and PSI ensures a continuous flow of electrons, driving ATP and NADPH production. The spatial arrangement of these photosystems within the thylakoid membrane is vital for efficient energy conversion and the overall process of photosynthesis.

VI. Electron Transport Chain and ATP Synthesis

The electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes embedded in the thylakoid membrane, facilitating the transfer of electrons released from Photosystem II. As electrons move down the ETC, energy is released, which is used to pump protons (H⁺) from the stroma into the thylakoid lumen, creating a proton gradient.

This proton gradient represents potential energy, driving ATP synthesis through a process called chemiosmosis. ATP synthase, an enzyme complex, allows protons to flow down their concentration gradient, back into the stroma. This flow powers the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP, a process known as photophosphorylation.

The ETC also receives electrons from Photosystem I, further contributing to the proton gradient and ATP production. Non-cyclic photophosphorylation involves both PSII and PSI, resulting in ATP and NADPH formation. Cyclic photophosphorylation, involving only PSI, generates additional ATP but no NADPH. Ultimately, the ETC and ATP synthase work in tandem to convert light energy into the chemical energy stored in ATP.

VII. Light-Independent Reactions (Calvin Cycle)

The Calvin cycle, occurring in the stroma of the chloroplast, utilizes the ATP and NADPH generated during the light-dependent reactions to convert carbon dioxide into glucose. This cycle doesn’t directly require light, hence the name “light-independent,” but relies on the products of the light reactions.

The cycle begins with carbon fixation, where CO₂ combines with ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), catalyzed by the enzyme RuBisCO. This unstable six-carbon compound immediately breaks down into two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA).

Next, in the reduction phase, ATP and NADPH are used to convert 3-PGA into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P), a three-carbon sugar. Some G3P molecules exit the cycle to be used for glucose and other organic molecule synthesis. Finally, in the regeneration phase, the remaining G3P molecules are used to regenerate RuBP, allowing the cycle to continue. For every six CO₂ molecules fixed, one glucose molecule is produced.

VIII. Carbon Fixation, Reduction, and Regeneration

Carbon fixation initiates the Calvin cycle, where atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into an organic molecule. Specifically, CO₂ combines with ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP), a five-carbon molecule, facilitated by the enzyme RuBisCO. This creates an unstable six-carbon intermediate that quickly splits into two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA).

The reduction phase then utilizes the energy from ATP and the reducing power of NADPH – products of the light-dependent reactions – to convert 3-PGA into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P). This is an energy-consuming step, transforming the initial carbon fixation product into a usable three-carbon sugar.

Finally, regeneration ensures the cycle’s continuation. Most of the G3P produced isn’t used to create glucose directly; instead, it’s employed to regenerate RuBP, the initial CO₂ acceptor. This complex series of reactions requires ATP and restores the starting molecule, allowing the Calvin cycle to repeat, continuously fixing carbon dioxide and producing more G3P.

IX. Factors Affecting Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis, while fundamental, isn’t a constant process; its rate is significantly influenced by several environmental factors. Light intensity is paramount, as it directly fuels the light-dependent reactions. Increasing light intensity generally boosts photosynthetic rate, up to a certain point, beyond which further increases yield diminishing returns, and can even cause photoinhibition.

Carbon dioxide concentration also plays a crucial role. As a key reactant in the Calvin cycle, higher CO₂ levels typically enhance photosynthesis, though this effect is often limited by other factors. Temperature exerts a complex influence. Enzymes involved in photosynthesis have optimal temperature ranges; rates increase with temperature up to a point, then decline as enzymes become denatured.

Water availability, though not directly part of the photosynthetic equation, indirectly affects it by influencing stomatal opening. Limited water causes stomata to close, restricting CO₂ uptake and hindering photosynthesis. Furthermore, irradiance, thallus temperature, and hydration all impact photosynthetic efficiency in various plant species.

X. Light Intensity, Carbon Dioxide Concentration, and Temperature

Light intensity’s effect on photosynthesis is a direct correlation, initially. As light increases, so does the rate of light-dependent reactions, driving ATP and NADPH production. However, this isn’t limitless; a saturation point is reached where further light exposure doesn’t increase the rate, and can even damage photosynthetic machinery.

Carbon dioxide concentration impacts the Calvin cycle, the light-independent reactions. Higher CO₂ levels generally lead to increased carbon fixation, boosting sugar production. However, this is often a limiting factor in natural environments, as CO₂ levels are typically lower than what plants can optimally utilize.

Temperature influences enzymatic activity, critical for both stages of photosynthesis. Enzymes have optimal temperatures; rates increase with warming until the optimum is reached, then rapidly decline as enzymes denature. The responses of photosynthesis to decreasing water content are also temperature-dependent, as observed in lichen species like Cladonia subtenuis.

These three factors interact, meaning the effect of one depends on the levels of the others.

XI. Cellular Respiration: Releasing Chemical Energy

Cellular respiration is the process by which organisms break down glucose and other fuel molecules to release energy in the form of ATP. This energy powers cellular activities, essentially reversing the energy capture of photosynthesis. It’s a fundamental process for all life, occurring in both autotrophs and heterotrophs.

Unlike photosynthesis, which stores energy, respiration releases it. This occurs through a series of metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. Each stage contributes to the overall ATP yield, with oxidative phosphorylation being the most significant producer.

The process requires oxygen (aerobic respiration) in most organisms, though anaerobic respiration and fermentation exist as alternatives in oxygen-deprived environments. These anaerobic pathways are less efficient, yielding fewer ATP molecules per glucose molecule.

Respiration is intricately linked to photosynthesis, utilizing the oxygen and glucose produced during photosynthesis, and releasing carbon dioxide and water as byproducts – the very inputs for photosynthesis. This creates a vital cycle of energy and matter.

XII. The Four Stages of Cellular Respiration

Cellular respiration unfolds in four key stages: glycolysis, the pyruvate oxidation, the Krebs cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle), and finally, oxidative phosphorylation – encompassing the electron transport chain and chemiosmosis. Each stage builds upon the previous one, progressively extracting energy from glucose.

Glycolysis, occurring in the cytoplasm, breaks down glucose into pyruvate, yielding a small amount of ATP and NADH. Pyruvate then undergoes oxidation, converting into acetyl-CoA, which enters the Krebs cycle.

The Krebs cycle, taking place in the mitochondrial matrix, further oxidizes acetyl-CoA, releasing carbon dioxide, ATP, NADH, and FADH2. These electron carriers then deliver high-energy electrons to the electron transport chain.

Oxidative phosphorylation, located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, utilizes the electron transport chain to create a proton gradient, driving ATP synthesis via chemiosmosis. This stage generates the vast majority of ATP produced during cellular respiration, making it the most crucial for energy production.

XIII. Glycolysis: Breaking Down Glucose

Glycolysis, meaning “sugar splitting,” is the initial stage of cellular respiration, occurring in the cytoplasm and not requiring oxygen. It’s a universal pathway found in nearly all organisms, suggesting its ancient evolutionary origins. This ten-step process transforms one molecule of glucose (a six-carbon sugar) into two molecules of pyruvate (a three-carbon molecule).

The process can be divided into two phases: the energy-investment phase and the energy-payoff phase. The energy-investment phase consumes two ATP molecules to activate the glucose molecule, making it more reactive.

Subsequently, the energy-payoff phase generates four ATP molecules, resulting in a net gain of two ATP per glucose molecule. Additionally, glycolysis produces two molecules of NADH, an electron carrier that will be used later in oxidative phosphorylation.

While glycolysis yields a small amount of ATP directly, its primary importance lies in producing pyruvate, which serves as the starting point for further energy extraction in aerobic respiration, or as a substrate for fermentation in anaerobic conditions.

XIV. Krebs Cycle (Citric Acid Cycle)

The Krebs Cycle, also known as the Citric Acid Cycle, is a series of chemical reactions central to all aerobic organisms. It takes place in the mitochondrial matrix, following glycolysis and before the electron transport chain. Prior to entering the cycle, pyruvate, produced during glycolysis, is converted into Acetyl-CoA, releasing carbon dioxide and generating NADH.

Acetyl-CoA then combines with oxaloacetate, a four-carbon molecule, initiating the cycle. Through a series of eight enzymatic reactions, Acetyl-CoA is completely oxidized, releasing carbon dioxide as a waste product.

Crucially, the Krebs Cycle generates a small amount of ATP (or GTP), but its primary function is to produce high-energy electron carriers: NADH and FADH2. These carriers will donate electrons to the electron transport chain, driving ATP synthesis.

For each molecule of glucose that initially underwent glycolysis, the Krebs Cycle occurs twice (once for each pyruvate molecule). This results in the production of two ATP molecules, six NADH molecules, and two FADH2 molecules per glucose molecule, preparing for the final stage of cellular respiration.

XV. Electron Transport Chain and Oxidative Phosphorylation

The Electron Transport Chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. It’s the final stage of aerobic respiration, utilizing the high-energy electrons carried by NADH and FADH2, generated during glycolysis and the Krebs Cycle.

As electrons are passed down the chain, from one protein complex to the next, energy is released. This energy is used to pump protons (H+) from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient.

This proton gradient represents potential energy, which is then harnessed by ATP synthase, an enzyme that allows protons to flow back into the matrix. This flow drives the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP – a process called oxidative phosphorylation.

Oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor in the ETC, combining with electrons and protons to form water. Without oxygen, the ETC would halt, and ATP production would drastically decrease. Oxidative phosphorylation generates the vast majority of ATP produced during cellular respiration, approximately 32-34 ATP molecules per glucose molecule.

XVI. Anaerobic Respiration and Fermentation

When oxygen is unavailable, cells can resort to anaerobic respiration or fermentation to generate ATP, though these processes are far less efficient than aerobic respiration. Anaerobic respiration utilizes an electron transport chain with a different final electron acceptor than oxygen, such as sulfate or nitrate, found in certain bacteria and archaea.

Fermentation, however, does not involve an electron transport chain. Instead, it relies on glycolysis to produce a small amount of ATP, followed by reactions that regenerate NAD+, which is essential for glycolysis to continue.

Two common types of fermentation are lactic acid fermentation, occurring in muscle cells during intense exercise, and alcohol fermentation, used by yeast to produce ethanol and carbon dioxide.

While fermentation allows cells to continue producing some ATP without oxygen, it yields only 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule, compared to the approximately 36-38 ATP molecules produced by aerobic respiration. Fermentation is crucial for various industrial processes, like brewing and baking.

XVII. Comparing Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are complementary processes that form the foundation of energy flow in ecosystems. Photosynthesis utilizes light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen, effectively storing energy in the bonds of glucose molecules. Conversely, cellular respiration breaks down glucose in the presence of oxygen to release energy, producing carbon dioxide and water as byproducts.

Essentially, the products of one process serve as the reactants of the other, creating a cyclical relationship. Photosynthesis removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, while cellular respiration returns it. This interplay maintains atmospheric balance and supports life on Earth.

While photosynthesis is an anabolic process (building up complex molecules), cellular respiration is catabolic (breaking down complex molecules). Both processes involve electron transport chains and ATP synthesis, but they occur in different cellular compartments – chloroplasts for photosynthesis and mitochondria for respiration.

Understanding this reciprocal relationship is key to grasping the interconnectedness of life and the importance of maintaining a healthy environment.

XVIII. Energy Flow and Nutrient Cycling

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are central to energy flow and nutrient cycling within ecosystems. Photosynthesis captures solar energy and converts it into chemical energy stored in organic molecules, initiating the flow of energy through food chains and food webs. This energy is then transferred to other organisms through consumption.

Cellular respiration releases this stored energy, allowing organisms to perform life functions. However, energy transfer is not 100% efficient; some energy is lost as heat at each trophic level, demonstrating the unidirectional flow of energy.

Nutrient cycling is also intimately linked to these processes. Carbon, for example, cycles between the atmosphere, organisms, and the Earth through photosynthesis (carbon fixation) and respiration (carbon release). Similarly, other nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus are incorporated into organic molecules by producers and released during decomposition and respiration.

These cycles ensure the continuous availability of essential elements for life, highlighting the crucial role of photosynthesis and respiration in maintaining ecosystem stability and sustainability.

XIX. The Role of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria

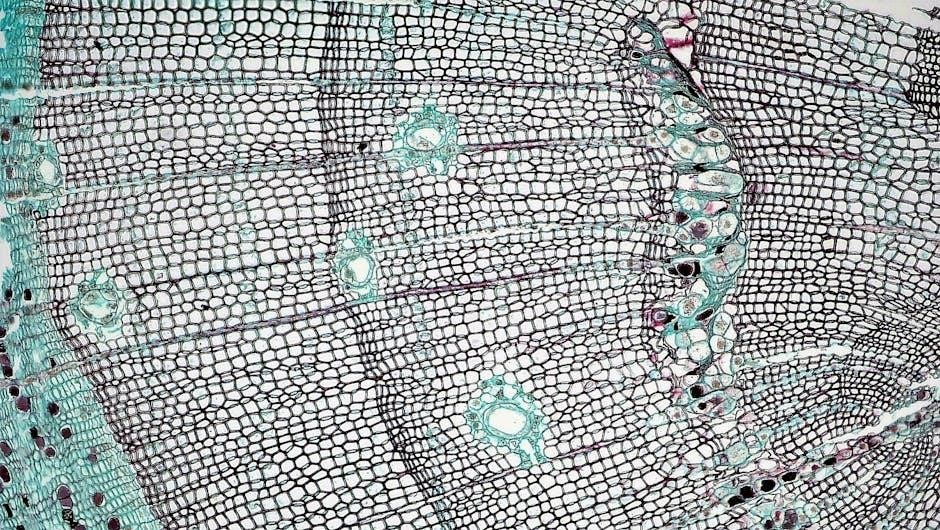

Chloroplasts and mitochondria are the key organelles responsible for photosynthesis and cellular respiration, respectively. Chloroplasts, found in plant cells and algae, contain chlorophyll, the pigment that captures light energy. Within their thylakoid membranes, the light-dependent reactions occur, converting light energy into chemical energy (ATP and NADPH).

The stroma, the fluid-filled space surrounding the thylakoids, is where the light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle) take place, utilizing ATP and NADPH to fix carbon dioxide into glucose.

Mitochondria, present in nearly all eukaryotic cells, are the sites of cellular respiration. Their inner membrane is folded into cristae, increasing surface area for ATP production. Glycolysis occurs in the cytoplasm, while the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain take place within the mitochondria.

These organelles work in a complementary fashion: chloroplasts capture and store energy, while mitochondria release it for cellular work. Their structural features are directly related to their specific functions in energy transformation.

XX. Real-World Applications and Importance

Understanding photosynthesis and cellular respiration has profound real-world applications. In agriculture, optimizing these processes can lead to increased crop yields through improved light exposure, carbon dioxide levels, and temperature control. Genetic engineering focuses on enhancing photosynthetic efficiency in plants.

Biofuel production relies heavily on photosynthesis, utilizing plants and algae to convert sunlight into energy-rich biomass. Furthermore, understanding respiration is crucial in medicine, particularly in studying metabolic disorders and cancer, where cellular energy processes are often disrupted.

Ecologically, these processes are fundamental to nutrient cycling and maintaining atmospheric balance. Photosynthesis removes carbon dioxide, mitigating climate change, while respiration releases it, completing the cycle. Lichen studies demonstrate how environmental factors impact these processes.

Ultimately, comprehending these biological mechanisms is vital for addressing global challenges related to food security, energy production, and environmental sustainability, impacting everything from plant biology to human health.